The Cello Concerto of Robert Schumann

Thoughts about the unusual history of Schumann's Cello Concerto

The big misunderstanding

The first time I played the Schumann Cello Concerto was in 1982 in Kuopio, Finland and the piece has been my favorite Cello Concerto ever since. I was always puzzled by many details in the piece that I felt were never played exactly as Schumann wrote them. When the Antonio Pacheco from Casa da Musica in Porto asked me to play Shostacovich's strange re-orchestration of this concerto I spent a lot of time trying to understand why anyone would want to re-write the piece. I came to the conclusion that for over 150 years this Concerto has been the subject of so many misunderstandings that it was inevitable someone would try to make an "improved" version of it.

The music of Schumann in general has had a lot of bad press and goes on getting it still today. His talent seems to be of a kind that is very difficult to make fit into what is expected of a great composer. In May 2010, when I played again Schumann's own version with Ernest Martínez Izquierdo and the Orquesta Sinfonica de Navarra I finally got the opportunity to try the Concerto as I thought Schumann wrote it. After that I have played it with several conductors and orchestras and the re-discovery continues.

The mystery of Schumann

Even today one often hears the opinion that Schumann's orchestration is in general defective and needs to be improved on. This received idea is so common that many conductors have never even thought of trying the original orchestration. In the end, as performances add on to the prejudices of previous generations, the real Schumann becomes more and more difficult to find.

First, the orchestra itself has changed a great deal since Schumann's days. As the string sections of the orchestras that Schumann wrote for were significantly smaller than today (in Leipzig: 9-8-5-5-4) the music does easily sound thick if played with almost twice the number of strings against the same number of winds. The strings used to be made of gut whereas nowadays they are of metal and optimised for maximum volume. Vibrato was used much more sparingly.

Second, Schumann's tempo's are treated with little or no respect. His original indications are often ignored, and the consensus seems to be that either he didn't know what he wanted or the metronome he used was faulty. The problem is that his indications are sometimes uncomfortably fast and at other times uncomfortably slow. There is clearly something more than a faulty metronome behind this. Something in the nature of Schumann's music allows it to almost fit within the accepted conventions, but not quite. The irregular phrase-structure goes often unnoticed, making especially the finales often sound simply repetitive, when in fact there is an subtle play of irregular phrase lengths which, if understood, brings the music alive.

Third, the rubato in his music often becomes heavy, especially in the concertos, where one hears a lot of slowing down, much less going forward. When the tempo fluctuations become too mannered, the irregularities and surprises get hidden and the very nature of the music altered. In the performances of the solo piano pieces one can hear more often the real Schumann whose music fluctuates between blissful peace and feverish anxiety,

It is surprising how difficult it is to gather enough curiosity to try out the music the way Schumann wrote it before changing it. Instead, we try to fit Schumann's very unconventional music to conventions that come from nowhere in particular. I admit I was myself guilty of this habit for years!

Schumann's chamber music with piano is also said to suffer from bad instrumentation, the piano supposedly written too much in the middle register making balance "impossible". Could the different piano of the time have been the reason for this kind of writing? Schumann wrote for the piano he knew, not the much more powerful instrument of today. If we today feel the music sounds bad on the instruments we use, we could study how the music sounded with the instruments he wrote it for and look for a similar balance on our instruments.

Many of the mysteries concerning Schumann are explained if one remembers that he was a pianist and not a string player. The phrasing and rubato are much clearer in most cases when one imagines it through the piano. Often one hears it said that Chopin's melodies have their roots the Italian opera and that to understand Mozart's music one has to listen to his Operas. The essence of Schumann is surely in his piano music.

It is in this general context that one can understand why re-orchestrations like the one of Shostacovich were attempted. There is an interesting article by the conductor Felix Weingartner, who describes in detail how Schumann's Symphonies are defective, but then goes on to give advice how they should be played. There seems to be a strange greatness in this music that made musicians want to make it acceptable even if they didn't really appreciate it. In time it becomes difficult to know the difference between a piece and its performance tradition in which each generation of musicians has added an extra layer of mannerisms.

A difficult beginning

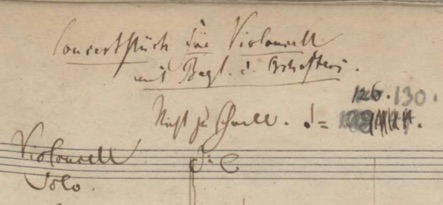

Schumann finished the "Concertstück mit Begleitung des Orchesters" on 24th October 1850, the same day he conducted his first concert with the Düsseldorf orchestra. He seems to have been happy about the piece and tried desperately to interest cellists in performing the piece - in vain. He had a piano rehearsal with the cellist and the concertmaster of the Düsseldorf orchestra in March 1851. Nothing resulted from that. He then asked, in October 1851, a well-known Düsseldorf cellist-composer Robert Bockmühl to read through the piece and help him in preparing the cello part for publication. From these meetings we can sense the beginning of the big misunderstanding.

Bockmühl initially showed some interest in performing the piece, but had also many reservations about it. He felt the tempo Schumann wanted for the first movement (crotchet=144) much too fast and asked it to be taken down to 96. Schumann agreed to take it down to 130, but no further. From this moment on Bockmühl started finding excuses to never play the piece, even if he eventually did edit the solo part, adding a number of simplifications of his own.

Two publishers (Friedrich Hofmeister and Carl Luckhardt) refused to publish the piece when Schumann offered it, only the third, Breitkopf & Härtel accepted it. Schumann described the Concerto to them as "really quite a jolly piece." Unfortunately for us, even Breitkopf & Härtel refused to publish the arrangement for String Quartet and cello that Schumann proposed (learning about this I have myself now realised a version for String Quartet and cello, useful for both student and concert purposes. This version can be ordered from www.petals.org). Neue Berliner Musikzeitung published a very negative review of the Concerto when it came out in piano reduction, complaining of some "rather curious harmonic progressions" and concluding that it "would not come off well as a concert piece".

As cellists showed no interest in performing the piece, Schumann made an arrangement for violin and gave it to Joseph Joachim, who promptly filed it away without ever playing it. It only turned up in 1987 in the Joachim archive. The same fate fell later on the Violin Concerto, which is supposed to have been located with the help of a medium in the 1930s.

The publishing of the Cello Concerto took place amidst dramatic circumstances just when Schumann's mental unstability erupted for the final time. The night when he started having auditory hallucinations he tried to calm the voices in his head by burying himself in the proof-reading of the Cello Concerto. He did indeed finish it and sent it off on the 21st of February 1854, six days later he threw himself in the Rhine. So, while the Concerto was not the last piece he wrote it is one of the last he saw all the way to its publication.

It is now established that the first performance of the Concerto took place on 23rd of April 1860 almost four years after the composers death. The soloist was Ludwig Ebert, the orchestra Großherzolighen Hofkapelle Oldenburg directed by its Konzertmeister Karl Franzen, Ebert also performed it with piano accompaniment on 9th of June in the celebration for Schumann's 50th anniversary. Ebert's earlier efforts to perform the work with the Kapellmeister August Pott didn't succeed as the Kapellmeister thought the piece "disgusting, horrible and boring".

The Oldenburger Zeitung published a complimentary anonymous review of the piece two days later, admitting though, that the piece was not very well rehearsed; the orchestra hadn't felt it deserved the time.

I have been trying to establish how the piece got known around the world; Bernhard Cossmann played the piece in Moscow 1867. From the files of the some of US orchestras I can see that the first US performance was in Boston 1888, Pablo Casals gave the first Cleveland performance in 1920, Gregor Piatigorsky the San Francisco premiere 1947 and Washington premiere 1956. As far as I have been able to find out, Piatigosky's recording made in London 1934 is the first one of the piece. Even if this is now one of the best known Cello Concertos it is not rare to see a gap of ten years between performances with the major orchestras.

The manuscript reveals several interesting details: The title Concertstück and the struggle with the metronome indication. 144 > 126 > 128 > 130

About performing the Concerto

Until today I still haven't had the occasion to hear anyone else play the first movement in the given tempo. 130 being a tempo that doesn't exist on the scale of a mechanical metronome, Schumann must have been adamant to not bring it down to 126. The solo sections are often played in tempos varying between 84 and 102 leading to quite distorted proportions in the whole piece. The slow tempo provokes soloists to embark on extreme rubati in order to keep the public's (and his own) interest alive. Conductors systematically speed up in the orchestral tutti, often beyond the given tempo which can make a very exciting effect, but also turns it into a different kind of piece with two completely different characters between the tutti and solo sections. To add to this, at some point it became fashionable to slow the end of the development section into a kind of mini slow movement, a habit that has no justification in the score. The fact that the composer called the piece Conzertstück indicates to me that he didn't conceive it as an expansive romantic first movement.

Even if the Langsam of the second movement is in general played not much slower than indicated (crotchet=63), it too has been heard in very slow tempos forcing conductors to subdivide to the point of almost losing any feeling of tempo. Already in the earliest recording from 1934, one can hear the violin pizzicatos being changed to arco. (The re-orchestration by Schostacovich changes all the strings from pizzicato to arco, gives the countermelody from the principal cello to the bassoon, adds a harp etc..) In the next section, Etwas Lebhafter, indicates to me a tempo close to that of the first movement and the following Tempo I brings us back to the tempo of the Langsam. The transition into the last movement used often to be played with a ritenuto even if it is marked Schneller und schneller (faster and faster).

It is often said that the last movement is the weakest in the piece, consisting of 'boringly obsessive repetitions of few short ideas'. This is largely due to performers not paying attention to the very intricate way of changing the lengths of phrases. Indeed, the piece can become an uninteresting series of repetitions of a six-note subject if one does not pay attention to this. In the middle section almost every phrase is of a different length, a four bar phrase being an exception. The indicated tempo (crotchet=114) is somewhat slower than what most cellists play. Played too fast it can lose some of its playfulness and sound like a not a very successful virtuoso piece.

The written out accompanied cadenza has also prompted numerous mistreatments. It used to be customary to add elaborate solo cadenzas, sometimes cutting the following transition to the Coda. In almost all performances one hears the following section, Im Tempo, start much slower and proceed to the final Schneller tempo with a gradual accelerando, which is not indicated. If one respects the Im Tempo indication, (crotchet=114), the final Schneller will take us to the tempo of the first movement, closing the circle.

What surprises me is how many of the established performance traditions go against clear indications in the score. After all these years it is sometimes difficult to persuade an orchestra to change their way of thinking about a piece in just one rehearsal. One gets the curious feeling of having to excuse oneself for going against the "tradition" simply because this process needs more rehearsal time. It took me 25 years to gather the courage to try out the written tempo of the first movement. Once I had decided to do it, I realised that the way of seeing and playing every note had to change. I needed to change the bowings, reduce vibrato but in return found many new colors. In the end, many of Schumann's original long bows not only became possible, they seem like the only possibility.

Now that I finally have been able to experience the Concerto the way (I think) it was conceived I am convinced that it is very different piece han the one I learned many years ago. The proportions make much more sense to me - I see it in one big movement with three sections. The fact that the theme of the first section comes back in the other sections makes much more sense. There is a new lightness and anxiety in the first movement, the second movement becomes as peaceful as only Schumann can be, while being simple and light. The original title Conzertstück seems very fitting to this "new" piece. I want to thank the conductors Esa-Pekka Salonen, Jukka-Pekka Saraste, Sian Edwards, Ernest Martínez Izquierdo, Oliver Knussen, Yasuo Shinozaki, Dima Slobodaniouk and most recently Brad Lubman in accompanying me on this quest for Schumann.

© Anssi Karttunen 2009-2015

Listen how the Schumann Cello Concerto sounds in Schumann's tempos.

Recording by Gabriel Schwabe with Lars Vogt conducting the Royal Northern Sinfonia