Hans Werner Henze's Lovesongs

Recording Henze's Englische Liebeslieder

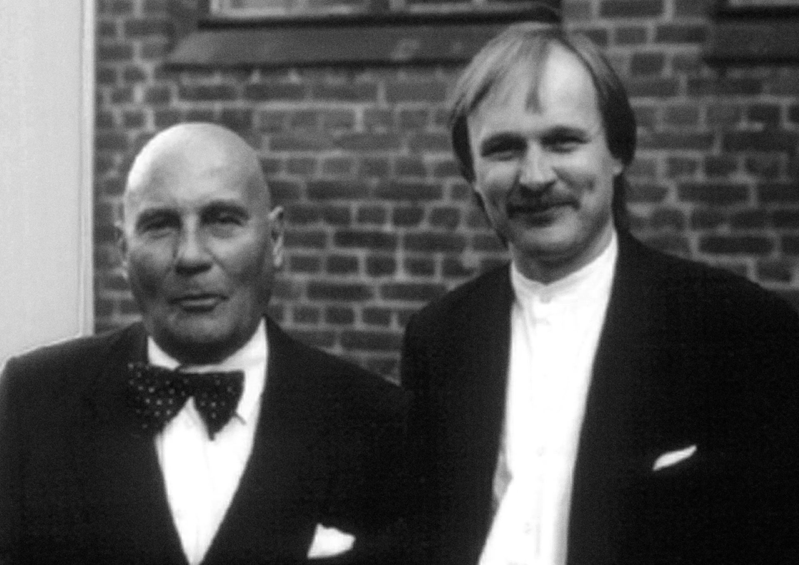

I was introduced to both Hans Werner Henze and Oliver Knussen after a concert where I played Magnus Lindberg’s Zona with the London Sinfonietta in 1990. Six years later, with Olly’s help, I persuaded Mr Henze to be composer in residence at the Suvisoitto Festival in Finland. I remained friends with both composers until the end of their lives.

At that festival I played Henze’s Introduction, Theme and Variations, based on a movement he extracted from his original Sieben Liebeslieder. On every occasion we met after that, he would ask if I could also play the Englische Liebeslieder. Although I would take out the score each time, the piece was so incredibly difficult and problematic that I simply couldn't imagine how to do it justice, or find a way to make the cello be heard above the orchestra.

Soon after Henze died, Olly called up and asked if I would play the piece with him and the BBCSO in a Henze memorial concert. I heard myself say - without hesitation - that naturally I would love to. I was surprised how I now saw the piece differently. It still looked difficult, but now that the composer was no longer with us, the piece had started to belong to the history of music. It just didn't seem right to be afraid of it.

Rather than pulling the piece apart and building up from the smallest detail as he might have been expected to do, Olly let the orchestra play it through a lot, every now and then asking one group to play alone. He allowed us hear the beautiful and delicate layers that were hiding under the mass of the music. Once we understood the importance of every single layer we all started listening differently, making sure to get out of the way when someone else had a special message. The whole orchestra began playing with a transparency that allowed the seemingly impossible detail to shine through. We could see not only the forest but also every tree and flower and even hear the birds. As a result we can now hear the piece as one of the most moving cello concertos ever written.

Olly also dug out the texts on which each lovesong is based. They bring to light Henze’s incredible sensitivity and culture. Just like the texts crossing over centuries and a multitude of styles, the music goes through a myriad of emotional and intellectual states, from the most delicate to the extremely violent. The last movement, based on Shakespeare’s Sonnet 128, is a good demonstration. It starts as an intimate duo for piano and cello, grows into the hugest symphonic tutti of any concerto, then distills via a macabre dance to a lonely solo cello and finally ends up as a string quartet.

Now that I no longer have the possibility to make music with my dearest and closest friend Olly I am so happy that that we can leave the recording of this very concerto as our joint testament. No one can match Olly's musicality, his curiosity, his knowledge. He was a musician with an X-ray vision which took him directly to the core of music and he would not accept anything that got in the way of delivering that message.

© Anssi Karttunen, Paris 2018

Hans Werner Henze: Englische Liebeslieder - texts that served as inspiration:

Even if Henze himself thought that knowing these poems is not necessary for the understanding of the piece I strongly think they are. It was only after Olly found them and sent them to me that I began really to understand the webs of meaning in each movement and the amazing variety of cultural references. The intimacy and tenderness of the music becomes all the more clear after reading the poems. AK

I

She Tells Her Love While Half Asleep

She tells her love while half asleep,

In the dark hours,

With half-words whispered low:

As Earth stirs in her winter sleep

And puts out grass and flowers

Despite the snow,

Despite the falling snow.

II

(music quoted: Why aske you, by Anon.

from the Fitzwilliam Virginal book)

John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester

All my past life is mine no more,

The flying hours are gone,

Like transitory dreams giv’n o’er,

Whose images are kept in store

By memory alone.

The time that is to come is not;

How can it then be mine?

The present moment’s all my lot;

And that, as fast as it is got,

Phyllis, is only thine.

Then talk not of inconstancy,

False hearts, and broken vows;

If I, by miracle, can be

This live-long minute true to thee,

’Tis all that Heav'n allows.

III

Blow, Blow, Thou Winter Wind (As you like it)

Blow, blow, thou winter wind

Thou art not so unkind

As man's ingratitude;

Thy tooth is not so keen,

Because thou art not seen,

Although thy breath be rude.

Heigh-ho! sing, heigh-ho! unto the green holly:

Most friendship is feigning, most loving mere folly:

Then heigh-ho, the holly!

This life is most jolly.

Freeze, freeze thou bitter sky,

That does not bite so nigh

As benefits forgot:

Though thou the waters warp,

Thy sting is not so sharp

As a friend remembered not.

Heigh-ho! sing, heigh-ho! unto the green holly:

Most friendship is feigning, most loving mere folly:

Then heigh-ho, the holly!

This life is most jolly.

For Hans Werner Henze the cello was an instrument often linked to love or death. His first piece for cello was Serenade from 1949. In 1953 he wrote his Ode to the West Wind for cello and orchestra, based on a poem by Percy Bysshe Shelley. The piece today known as Englische Liebeslieder was originally called Sieben Liebeslieder, written 1984-85. After the first performance in 1986 in Cologne by Heinrich Schiff, David Shallon and the WDR Symphony Orchestra Henze decided to take out one of the movements. Eventually he elaborated that movement and published it in 1992. It became the Introduction, Theme and Variations for cello, harp and strings.

Apart from these pieces Henze also wrote a solo cello piece Epitaph (1979) in memory of Paul Dessau. For Paul Sacher's 75th birthday he wrote a piece which he then elaborated into Capriccio for solo cello (1981). In 1997 he wrote Trauer-Ode für Margaret Geddes for 6 cellos.

You can listen to Anssi Karttunen play Henze's music here: Englische Liebeslieder, Serenade, Introduction, Theme and Variations, Trauer-Ode für Margaret Geddes.

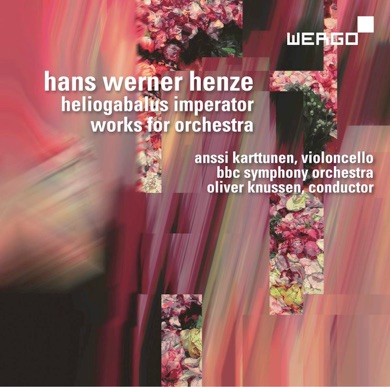

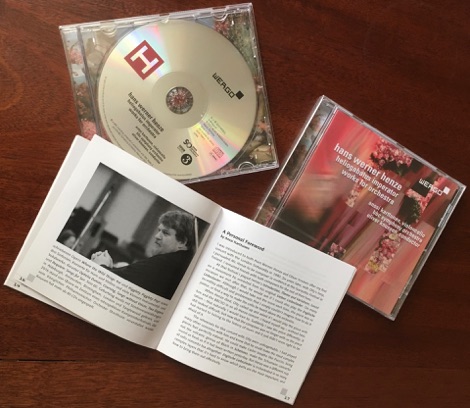

Englische Liebeslieder is available on Wergo WER 73442.

IV

Sleep now, O sleep now,

O you unquiet heart!

A voice crying "Sleep now"

Is heard in my heart.

The voice of the winter

Is heard at the door.

O sleep, for the winter

Is crying "Sleep no more."

My kiss will give peace now

And quiet to your heart -- -

Sleep on in peace now,

O you unquiet heart!

V

VI

How oft when thou, my music, music play’st,

Upon that blessed wood whose motion sounds

With thy sweet fingers when thou gently sway’st

The wiry concord that mine ear confounds,

Do I envy those jacks that nimble leap,

To kiss the tender inward of thy hand,

Whilst my poor lips which should that harvest reap,

At the wood’s boldness by thee blushing stand!

To be so tickled, they would change their state

And situation with those dancing chips,

O’er whom thy fingers walk with gentle gait,

Making dead wood more bless’d than living lips.

Since saucy jacks so happy are in this,

Give them thy fingers, me thy lips to kiss.

photo: © Muriel von Braun