Finding Dvorak's Cello Concerto

I studied the piece over 30 years ago with three of my teachers: William Pleeth, Jacqueline du Pré and Tibor de Machula. By now my memories of those lessons are already somewhat confused. I remember details from each of the lessons but I can't remember who really would have influenced my understanding of the piece. That was a job left for myself for later. I was asked to play the piece only a couple of times during the following 30 years, without really studying it anew. Now the moment had finally arrived to get to the task.

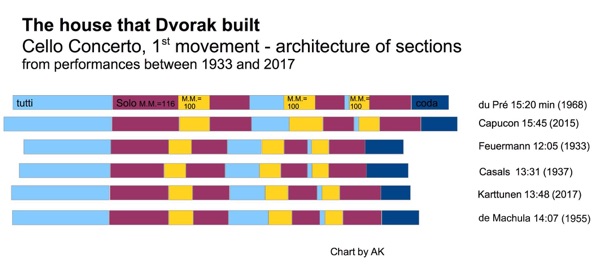

I spent 8 months studying the new edition, practicing, listening to every possible recording starting from the very first ones by Emmanuel Feuermann and Pablo Casals up to the latest versions by cellists much younger than I. The first thing I noticed was the amazing lengthening of the piece from Feuermann's 33:30 to sometimes more than 45 minutes. Even between the recordings of two of my own teachers, Tibor de Machula and Jacqueline du Pré there is a difference of over 10 minutes. I had to find out where all that disagreement came from.

Somewhere around the 1960's string players were noticing that audiences react well to two things, stretching the tempo and concentrating on extremes of dynamics; as loud as possible and as soft as possible. It also became common to announce a upcoming surprise by slowing down before it or higlighting an emotion with an extreme dynamic. Subtleties like trusting the written dynamics, expressions or tempos seemed not to be enough.

It seems to me that cellists make their decisions about tempos more and more according to what feels effective rather than thinking what the piece requires, ignoring the composer's indications if necessary. And when someone has played one passage very slowly, the next one tries if it could be done even slower for even more effect.

Many interpretations are reactions or commentaries to other interpretations rather than attempts to understand the composer's vision. They are also built from details up rather than from the architecture down to the details.

Understanding architecture

I used to wonder why there are performers who manage to give a strong sense of form and inevitability to their performances. In a piece like this it seems to me that this has to do at least to a large part with how one treats the tempo and structure. It can also be done through giving sections similarity in character, but in some way one needs to give the listener a feeling of recognition of similarity and difference.

In this Concerto the tempo changes frequently, sometimes through slowing down or speeding up, but often also suddenly. For example the first movement has a main tempo of (116), three sections that are marked to slow down to (100) and one piu mosso in the coda to (132). If one observes that the sostenuto sections are all in the same tempo one has a feeling of recognition of the tempo, even if each section has different emotional content. If, on the other hand, one gives in to the temptation to play the second sostenuto section much slower than the other two, one important feeling of familiarity disappears. The question is not of being academic about the metronimical difference between the main tempo and the sostenuto. One needs to feel the similarity in the difference.

One of the most interesting examples is in the slow movement; the poco accelerando that starts in ms. 30 can seem confusing because, while it is very passionate and gets faster, Dvorak also asks a diminuendo and then drops suddenly to Tempo I. Dropping into a slower tempo after getting faster and softer seems to be a contradiction, but should it really be?.

The differences in dynamics in the new Urtext edition are sometimes very subtle, sometimes surprisingly drastic. In the first movement the end of the famous arpeggio passage finishes with a crescendo rather than the well known diminuendo and (unwritten) ritenuto. In the slow movement the several little crescendos and diminuendos have been shifted (ms 13, 16, 80, 120 etc.). They may seem to go against the dynamics of the orchestra, but this time at least I felt they were perfectly natural.

In the last movement there is again one main tempo (104) and this time two slightly different slower sections (92 and 84). In between one should feel the familiarity of the return to the original tempo. The most rarely observed return to the main tempo is in the coda, which is mostly already begun in a slower tempo and then taken to such extremes of slowness that in the end, when Dvorak finally writes molto ritenuto that one can't possible slow down any more. Dvorak's indication is to start In Tempo (104) and slow down in two stages (to 84 and 76).

Leave me alone!

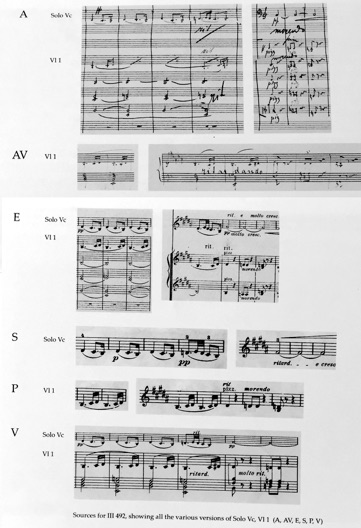

One can see from the different sources that Dvorak struggled with countless variants of the indications to get this ending just right. I now feel that the lonely f-sharp is really an incredibly dramatic moment in a personal tragedy that Dvorak lived once he already thought to have finished the piece. It is like a black hole into which all the drama of the piece is sucked.

Soon after this Concerto Dvorak stopped writing abstract orchestral music and preferred symphonic poems with very strong programmatic stories, it is not suprising that his need to tell a story is already there at this dramatic moment of the concerto and his life.

Carefully observing the composer's instructions doesn't mean giving up on freedom, I find it does the contrary. There are always - also in this concerto - enough questions to which there are no absolute answers for one to try different solutions each time. But it is much easier to feel free when one is has as much information as possible about the world behind the notes.

Change is a long process, patience is in the end the virtue that really matters. All those performances, however different from mine are part of the long life of the piece. Like the great paintings, pieces gather dust and the colors fade but every now and again someone comes along and does some restoraution work and the process starts again afresh.

Reading about the sources of the Cello Concerto makes it clear that the collaboration between Dvorak and Wihan was much closer than is generally known. Wihan made many corrections directly into the manuscript (which can now be consulted in ISMLP) and it is sometimes not possible to know who came up with the final version. This rings some very interesting bells in my own head. I know that one day some future musicologists will have at least as much trouble with some pieces with which I have been involved as a first (or second) performer. I am ever more convinced that knowing all the music and understanding the style of a composer are vital in understanding anything that one sees on paper.

Anssi Karttunen, 4.6.2016, Paris

A link to my similar study of the Schumann Concerto