Remarks on playing Bach

How to decide the tempos? How to decide the dynamics? What bowings should one use? What fingerings should one use? What are the articulations? What is my style?

These are some of the questions we have to ask ourselves when playing the Bach cello suites. It can be seem very mysterious to look for the right answers and possibilities seem endless. Instead of pretending that with my mere instincts I can discover a perfect logic, I have tried to find all the help that is available from literature, the manuscripts and studying the differences between the modern and baroque cello, bow and strings.

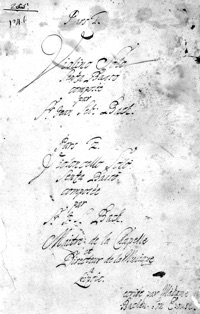

Editions

Most of the printed editions are useful in understanding the cellists who made the editions, but less useful in revealing much about Bach. Even the one's calling themselves Urtext edition disagree with each other and prove that one tends to see what one hopes to see. The most recent Bärenreiter Urtext edition at least offers all the existing manuscript sources and the varying readings.

As the manuscript of Bach himself is still lost we have to decide whether to trust one of the four early manuscript copies or any of the later editions which claim various degrees of authority. Since Anna Magdalena Bach's manuscript copy was most probably done at the very home of the composer I find her copy to have the most obvious authority. We can compare her manuscript with her copies of other works of Bach's where the original still exists. From them we can see that she was a very good copyist who - like everyone - made mistakes.

I have recently understood that the most useful document for us is actually Anna Magdalena's copy of the Violin Sonatas and Partitas. Comparing her copy to Johann Sebastian's own we can see that if only her copy existed, it would leave the violinists with the same kind of uncertainties and ambiguities as her copy of the cello Suites.

Obviously without the original we can't be sure where Anna Magdalena's mistakes are in the cello Suites, but knowing how her slurs differed from his in the violin pieces one can form a personal idea. After I made this discovery I realised that I had to abandon my long conviction of taking AMB's phrasings literally. Yet another example that one has to be ready to change one's convictions at any moment.

Tempo

The idea of Tempo Giusto was a common concept in the Baroque era, similar movements usually were played in similar tempos unless otherwise stated. A lot of help can be found by looking at the Suites as a cycle and reading carefully the manuscript of Anna Magdalena Bach. One can first consider all Preludes together and look for a tempo that would work for all of them. It is obviously not necessary for them to be metronomically the same, but a unity of tempos is very helpful..

It is revealing how similar movements can work in similar tempos. The alla breve marking of the 4th Prelude fits into this scheme. After looking at the preludes we can move on to the dance movements and look at each of them also in relation to other suites and the time signature. We see, for example, that the 1st and 4th Allemandes are also alla breve and therefore it is clear that they are faster than the other four.

We can also find information about how these dances would have been danced. These suites were obviously not meant to be danced, but one should not play, for example, a Sarabande in a tempo so slow that one couldn't possibly even try to dance to it. Following these simple means of deduction one can find out a lot about the tempos and eliminate a lot of un-stylistic extremes.

The 5th Suite is different from the others in several ways, obviously because of the scordatura and the fact that it is the only "French" Suite. Knowing the difference between the Italian Corrente (which would be a more correct title for the other Courantes) and French Courante is very important in deciding the tempo, the Courante being partly in two and partly in three, which makes it a much more complex and necessarily slower than Corrente. The lute transcription manuscript which is said to be by Bach himself makes some things easier to understand. Some of the rhythmic complexities that can only be guessed in the cello version are much clearer in the lute version.

Dynamics

Although Bach wrote only two dynamics in all of the suites - f and p in the Prelude of the 6th suite - we know some fundamental principals on the use of dynamics in his time. The one rule above all others is that dissonance was always stronger than consonance. With this simple rule one can build a map of dynamics built on the degree of dissonance at any moment. If one considers that going away from "home" is tension - stronger - and returning "home" is release - softer - the architecture of the music is immediately more clear. The result will be surprisingly different from a standard 20th century habit of following a melodic line.

One can also ask oneself if the forte and piano markings in the 6th Prelude mean that in similar repeated passages one should use these terraced dynamics or is he telling us in a subtle way exactly the opposite. Could he be saying that it was not a given?

Structure

Analysing the phrase structure is another very useful method to eliminate some questions. If one pays attention to where a phrase ends and the next one begins, one immediately knows where to breath. Understanding when the structure is even and when it is uneven makes it easier to avoid confusing the listener with an arbitrary rubato. Obviously the point is not to make a caricature of pointing out every phrase, but knowing and feeling the structure helps understanding. One often hears that the players haven't thought of the phrases in the dance movements. When you combine the attention to phrases with some basic knowledge about the particularities of each dance and the use of rhythmic devises such as hemiolas, one can see the complexity of Bach's world. Bach uses hemiolas very often in all of the suites to lend ambiguity to the phrases, sometimes they are hidden and can be subject to discussion, but looking for them is fascinating.

Phrasing

The most useful help can be found by looking at the manuscript copy of the solo violin works Anna Magdalena and comparing it to Bach's own manuscript . Most of the time when her slurs are ambiguous, his are not. Most of the time where she might seem to be suggesting a changing bowing, he doesn't. Obviously we can know what exactly would have been his phrasings for the cello, but we can make educated guesses and experiment. Looking at the violin manuscripts I feel it is clear that Anna Magdalena's inconsistences are very similar in both the violin and cello works and therefore Bach's own logic would also remain the same.

I have decided myself to base myself on the AMB manuscript and imagine where Bach would have been more consistent. There are almost always several possibilities so one has to constantly experiment and there is no guarantee that any particular guess is the same than Bach's.

Wrong notes

Every edition and cellist has to also make some decisions about notes that seem like mistakes. Some of them actually sound right or wrong only because we have heard generations of cellists follow someone else's "correction". Many of the uncertainties can already be verified if one understands the way Bach used accidentals. He did not repeat an accidental on consequent notes even if there is a bar-line in between and mostly not within a beam. There are no naturals unless the note is within the same beam but he did repeat an accidental within a measure on a separate beam. These rules are slightly different to those in use in later centuries and automatically a few readings will differ. There are more "mistakes " than elsewhere in the 5th Suite because of the scordatura and the fact that Bach notated in tablatura. AMB must have been humming the music as she copied and forgotten sometimes to allow for the transposition. Luckily we do have Bach's manuscript of the Lute transcription to check the differences.

Baroque cello, baroque bow, gut strings

If one only plays Bach on a modern bow it is impossible to know what the vocabulary for articulations was. As soon as one takes up a baroque bow one notices that certain things disappear and new ones appear in the vocabulary. Certain comfortable modern staccatos or a jumping bow (for example in the c major Courante) is less natural on a baroque bow. Fast separate bows (such as in the d minor Courante) stay much more on the string and speed becomes a pleasure and not a virtuoso showcase. Playing chords in any direction is much easier and it is soon evident that the modern square way of playing a chord gives way to a round, more balanced harmony. Even the seemingly constantly changing bowings of Anna Magdalena feel more approachable when the articulation is more flexible. If there is no baroque bow at hand one can get very close to the feeling by holding the modern bow about five centimetres closer to the middle of the bow. This changes the balance and makes the tip lighter, making it much easier to look for the right articulations.

The gut strings change a lot in the way this music sounds. They speak rather with the speed of the bow than with a sharp accent. The use of open strings is more natural. It is also clear that the resonance of the open strings is something that all baroque and classical composers knew how to use to great effect. I feel often that it creates a kind of a pedal for the cello, I often look for fingerings where I can leave the notes of a chord resonating to emphasize the dissonance or consonance. Using devices such as harmonics or higher positions sound most of the time out of place, like special effects. On the gut strings colour and resonance change even more than on metal strings and the longer resonance of the lower positions seems more appropriate to this music.

I encourage everyone to practice Baroque and Classical music holding the cello without the end-pin to learn how one's relation to the whole instrument changes. If one uses a long end-pin the instrument is more immobile and the flexibility of bowings is not easy to achieve.

The understanding of how to use vibrato with real meaning is also helped a lot by the baroque bow and gut strings. If one uses too much vibrato, the use of open strings sounds out of place, they stand out as being different. Expression is so easy to achieve with the baroque bow and gut strings that it seems a pity to spoil it with too much vibrato. Vibrato tends to mute the subtleties of bowing. It is useful to reverse the use of vibrato, to think that the norm is no vibrato and look for places where it might be a useful colour.

Conclusion?

These thoughts hopefully help to eliminate some of the questions and mysteries in playing Bach. There is no conclusion, no lasting truth, just convictions that last the duration of one performance after which we have to go back to questioning everything all over again.

© Anssi Karttunen 2016-2022